Modern machines are increasing in their complexity: it is common to have multiple GPUs attached to a single node, and multiple GPU-accelerated nodes connected by different interconnects throughout the memory hierarchy, such as NVLink within a single node and Infiniband across multiple nodes. As machines have become more complicated, developing software that achieves high performance on these machines has also become more difficult than before. Programmers must reason about how their program data is partitioned and distributed across GPUs and how to utilize the proper communication APIs to move data between memories in their machine, all while overlapping as much computation with data movement as possible. We find that many practitioners who could significantly benefit from the compute power of distributed and heterogeneous machines, such as domain scientists or data analysts, do not have the expertise needed to do so.

Legate is a software ecosystem being developed at NVIDIA and Stanford University that aims to make high performance computing (HPC) accessible to mainstream programmers, rather than just the small domain of HPC experts. The Legate project is working towards this goal in two main fronts: 1) building a runtime system (called the Legate Core) that automates away many of the difficulties in developing distributed software, and 2) building distributed replacements for popular high level libraries like NumPy (cuNumeric) and SciPy Sparse (Legate Sparse) that automatically scale to clusters of GPU-accelerated nodes. One of the key features that Legate enables for these libraries that differs from other distributed implementations is that Legate libraries can seamlessly share distributed data with each other, similarly to how the sequential versions of these libraries can. I’ll come back to this point in more detail later.

In this blog post, I’ll discuss both of these efforts (runtime system and library development). I’ll start first with highlighting some Legate libraries and their capabilities before diving into the Legate runtime itself. In terms of the target audience, the first section of this post should be approachable to end users looking to accelerate and distribute programs using common Python libraries. The second section lifts the curtain by looking at how Legate libraries are implemented with the Legate runtime, and is tailored to a more technical audience with some knowledge about distributed programming. By end of this blog post, the reader should have a good idea about some powerful Legate libraries and a high level idea about how to develop their own libraries using the Legate runtime.

Legate Libraries

cuNumeric

cuNumeric is a Legate library that aspires to be a drop-in

replacement for NumPy, automatically scaling NumPy programs across clusters of GPUs. The simplest

example to demonstrate this is the Python program below. The program tries to import cuNumeric, and

if it fails, falls back to NumPy. The program creates a 2-D array, and performs a 5-point stencil

computation over each cell by referencing aliasing slices of the grid array.

try:

import cunumeric as np

except ImportError:

import numpy as np

grid = np.random.rand((N+2, N+2))

# Create multiple aliasing views of the grid array.

center = grid[1:-1, 1:-1]

north = grid[0:-2, 1:-1]

east = grid[1:-1, 2: ]

west = grid[1:-1, 0:-2]

south = grid[2: , 1:-1]

for i in range(niters):

avg = center + north + east + west + south

work = 0.2 * avg

center[:] = work

When this program is run with cuNumeric, NumPy arrays are partitioned into tiles across the GPUs

of the machine, and operations like addition and multiplication are distributed so that each GPU

performs the operation on its local piece of the data. Additionally, communication between the aliasing views

of the grid array is automatically inferred by cuNumeric through Legate. After the operation

center[:] = work, the update to the center array must be communicated to the north, east, west

and south arrays. cuNumeric performs this communication automatically, discovering a halo-like

communication pattern between GPUs, where only the data at the edges of each tile needs to be communicated.

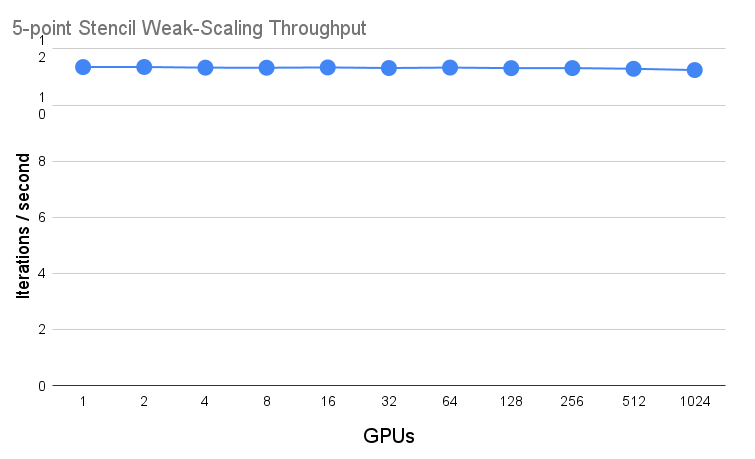

With cuNumeric and Legate, this Python program can weak scale with high efficiency to large numbers of GPUs. Below is a weak scaling plot of the stencil program out to 1024 GPUs. In weak-scaling, we start with a fixed problem size on a single GPU, and then increase the number of GPUs while keeping the problem size per GPU the same. We then plot the throughput per GPU achieved by the system. An ideal weak-scaling plot is a flat line that maintains the same throughput achieved at a single GPU 1, meaning that we could run the application on a problem size \(P * N\) on \(P\) GPUs in the same amount of time as problem size \(N\) on 1 GPU.

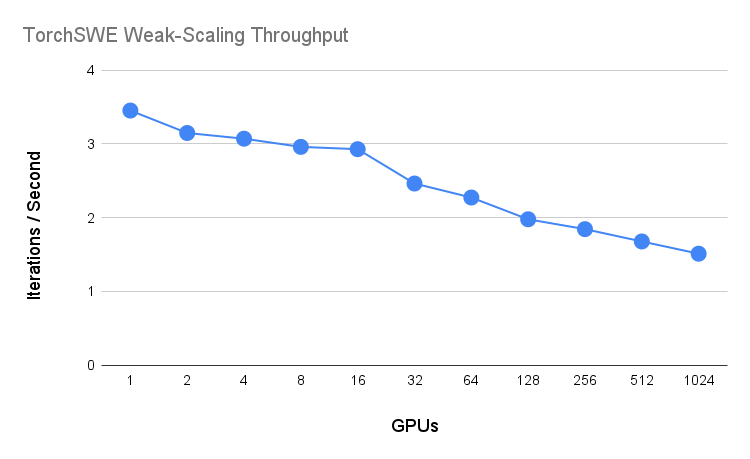

While the shown example is a very small program, we have been able to port large scientific applications to cuNumeric. The largest example to date is TorchSWE, a GPU-accelerated shallow-water equation solver developed by Pi-Yueh Chuang and Lorena Barba. The original version of the application used CuPy for GPU operations and MPI for distribution. The Legate team ported TorchSWE to cuNumeric by removing all of the MPI code and letting cuNumeric and Legate perform all distribution and communication. The resulting pure NumPy code when run with cuNumeric yields respectable weak-scaling performance, as seen below. Importantly, cuNumeric allows domain scientists with knowledge about physics to develop simulations in a high-level language like NumPy, and then execute that same code with high performance on a cluster of GPUs without expert knowledge of MPI.

While I’ve mostly touched on scientific use-cases of cuNumeric so far, we are also working with users of cuNumeric who are applying it to large data analysis workloads. cuNumeric supports a large subset of NumPy and has a unique set of features, which is (to my knowledge) not offered by any other competing distributed NumPy replacement. cuNumeric is an NVIDIA supported product with a beta release tag, and I encourage you to give it a try! For readers interested in more details about cuNumeric, please check out the SC 2019 publication.

Legate Sparse

Similarly to cuNumeric, Legate Sparse is an aspiring drop-in replacement for SciPy Sparse that scales Python programs operating on sparse matrices to clusters of GPUs. There are a number of libraries that offer distributed sparse linear algebra (PETSc, Trilinos), so just providing a distributed implementation of SciPy Sparse (despite the friendly Python API) is all that interesting by itself. The really interesting aspect of Legate Sparse is that it is an independently written distributed library that composes with cuNumeric to provide distributed NumPy and SciPy Sparse capabilities. An example of this composition is shown below by a program that either imports both cuNumeric and Legate Sparse or NumPy and SciPy Sparse, and then uses the Raleigh Quotient to estimate the maximum eigenvalue of a matrix.

try:

import cunumeric as np

import legate.sparse as sp

except ImportError:

import numpy as np

import scipy.sparse as sp

# Generate a random positive semi-definite matrix

A = sp.random(n, n, format='csr')

A = 0.5 * (A + A.T) + n * sp.eye(n)

# Estimate the maximum eigenvalue of A

x = np.random.rand(A.shape[0])

for _ in range(iters):

x = A @ x

x /= np.linalg.norm(x)

result = np.dot(x.T, A @ x)

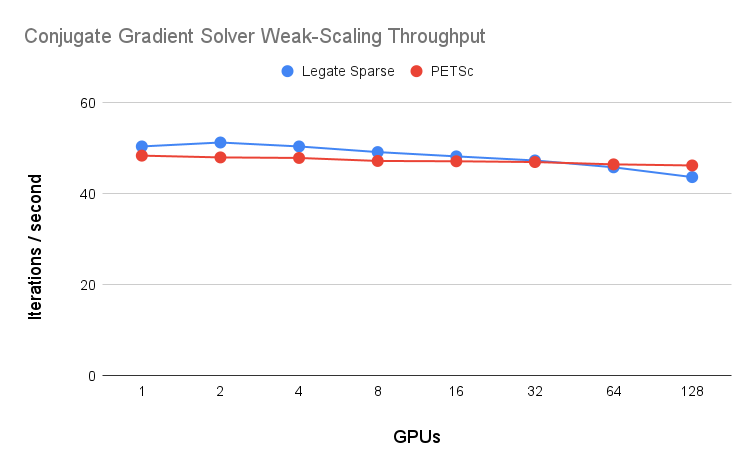

Dense and sparse arrays created by cuNumeric and Legate Sparse are distributed across all GPUs in the target machine. In the program above, distributed vectors created by cuNumeric are passed into Legate Sparse operations, which produce distributed data passed back to cuNumeric. This level of seamless composition between distributed libraries is almost never seen in distributed, high performance computing. Legate Sparse is able to achieve this interoperability while delivering competitive performance with state-of-the-art sparse linear algebra libraries like PETSc. A weak-scaling plot comparing the throughput achieved in a Conjugate Gradient solve by Legate Sparse and PETSc.

We’ve developed some complex pieces of code that use Legate Sparse and cuNumeric together, including geometric and algebraic multi-grid solvers, a sparse matrix factorization algorithm, and a Runge-Kutta integration method. Legate Sparse is currently in the process of transitioning from a research prototype to an NVIDIA-supported library. The most interesting pieces of Legate Sparse are actually the components inside the Legate runtime that were key to achieving performant composition with cuNumeric. I’ll discuss these components next in the blog post, but they are also covered in depth (along with other ideas behind Legate Sparse’s design) in the SC 2023 publication.

Legate Core

Having discussed some user-facing Legate libraries, I’ll now discuss how these libraries are implemented using the Legate runtime. The concepts I’ll introduce about the Legate runtime are not necessary to understand in order to use the user-facing Legate libraries like cuNumeric and Legate Sparse. However, they are important to understand if the reader wants to learn about the internals of these libraries, or wants to develop Legate libraries of their own.

The Legate runtime (called the Legate Core) is the glue that enables independent Legate libraries to share distributed data and abstracts away many details about distributed computing, such as data movement and synchronization. Categorically, Legate Core is a task-based runtime system with a distributed data model. What this means is that Legate Core has two fundamental abstractions for programmers, where the first abstraction is how programmers define computations, and the second is how programmers define their data. A Legate Core program organizes its computation into tasks and maps distributed data onto stores.

Legate Core represents distributed data as stores, which are distributed multi-dimensional arrays. Stores provide a global view to distributed data, and the Legate Core manages how stores are partitioned and distributed across the machine. Libraries built on top of Legate Core represent their distributed data structures with one or more stores. For example, cuNumeric arrays correspond to a single store, while Legate Sparse sparse matrices correspond to a collection of stores (the distributed CSR format packs together three stores).

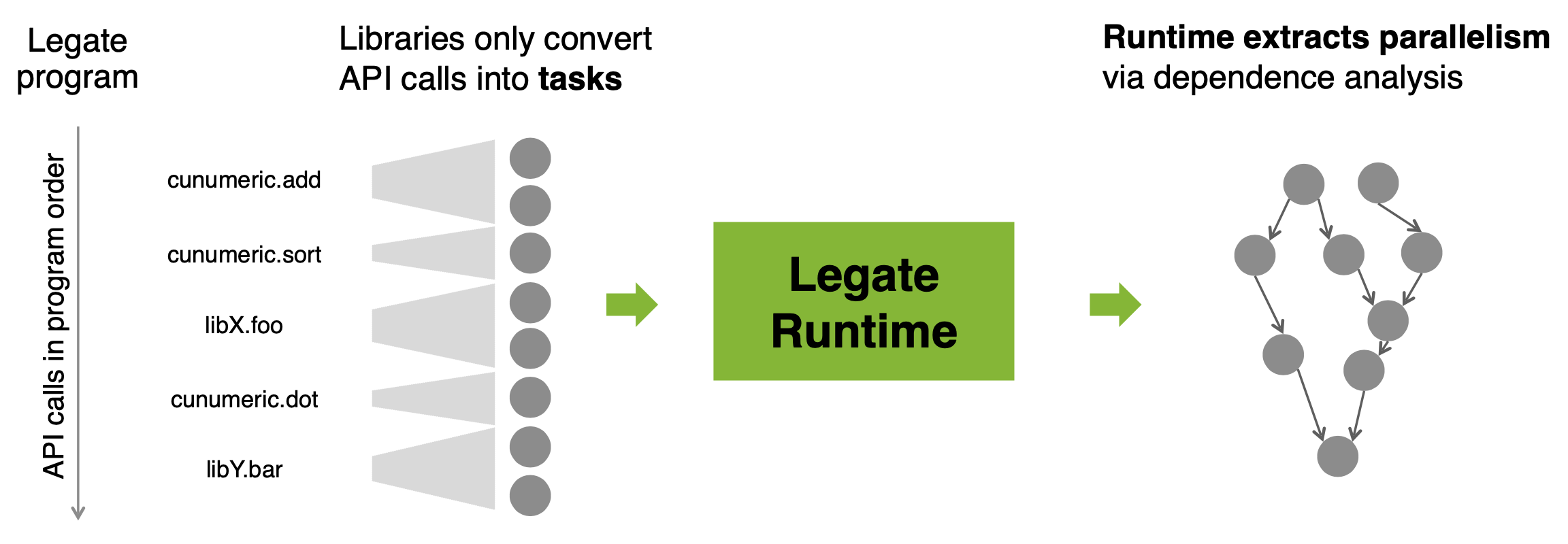

Tasks are designated functions registered with the Legate runtime that take stores as arguments. When a task is launched, the task describes in what ways it will use its argument stores, i.e. whether it will read from, write to, or reduce to each argument store. As tasks are launched into Legate Core, the runtime performs a series of analyses that automatically partition stores into pieces for distributed execution, find dependencies between tasks to extract parallelism, and insert communication between processors to keep store data up to date.

The abstract program representation of tasks and stores is key to the automation and composability provided by Legate. Legate libraries express only what computations must be performed, and are thus free of explicit synchronization and data movement. This freedom enables the Legate Core to weave together tasks from multiple different libraries into a single consistent execution, and find the necessary synchronization and data movement required across library boundaries.

To concretize some of these concepts and to introduce a key Legate concept called partitioning constraints,

I’ll walk through some Legate code involved in cuNumeric’s implementation of NumPy’s element-wise array addition operation.

In this code, I’ll assume the simplification that numpy.ndarray is represented directly as a legate.Store.

def add(A: legate.Store, B: legate.Store) -> legate.Store:

runtime = get_legate_runtime()

# Create the output array.

C = runtime.create_store(A.shape, A.dtype)

# Create a task.

task = runtime.create_task(CUNUMERIC_ADD_TASK_ID)

# Describe how the task will operate on stores.

task.add_input(A, B) # Read from A and B.

task.add_output(C) # Write to C.

# Constrain the partitioning of stores.

task.add_equality(A, B, C)

# Issue the task into the runtime.

task.execute()

The Legate Core runtime exposes a Python interface, which is used for launching work into the runtime system. The

shown code creates a task, declares that it will read from the two input stores A and B, and will write to

the output store C. Before issuing the task to the Legate Core, the code adds a partitioning constraint on the

task that states that partitions used for A, B and C must be the same. Intuitively, when doing an element-wise

addition, we need to be able to access the same element within each of the arrays, so the way that each of the arrays

are partitioned across the machine needs to be same. Because the Legate Runtime manages the way that stores are

partitioned, the partitioning constraints supplied on tasks control in what ways the Legate Runtime can choose

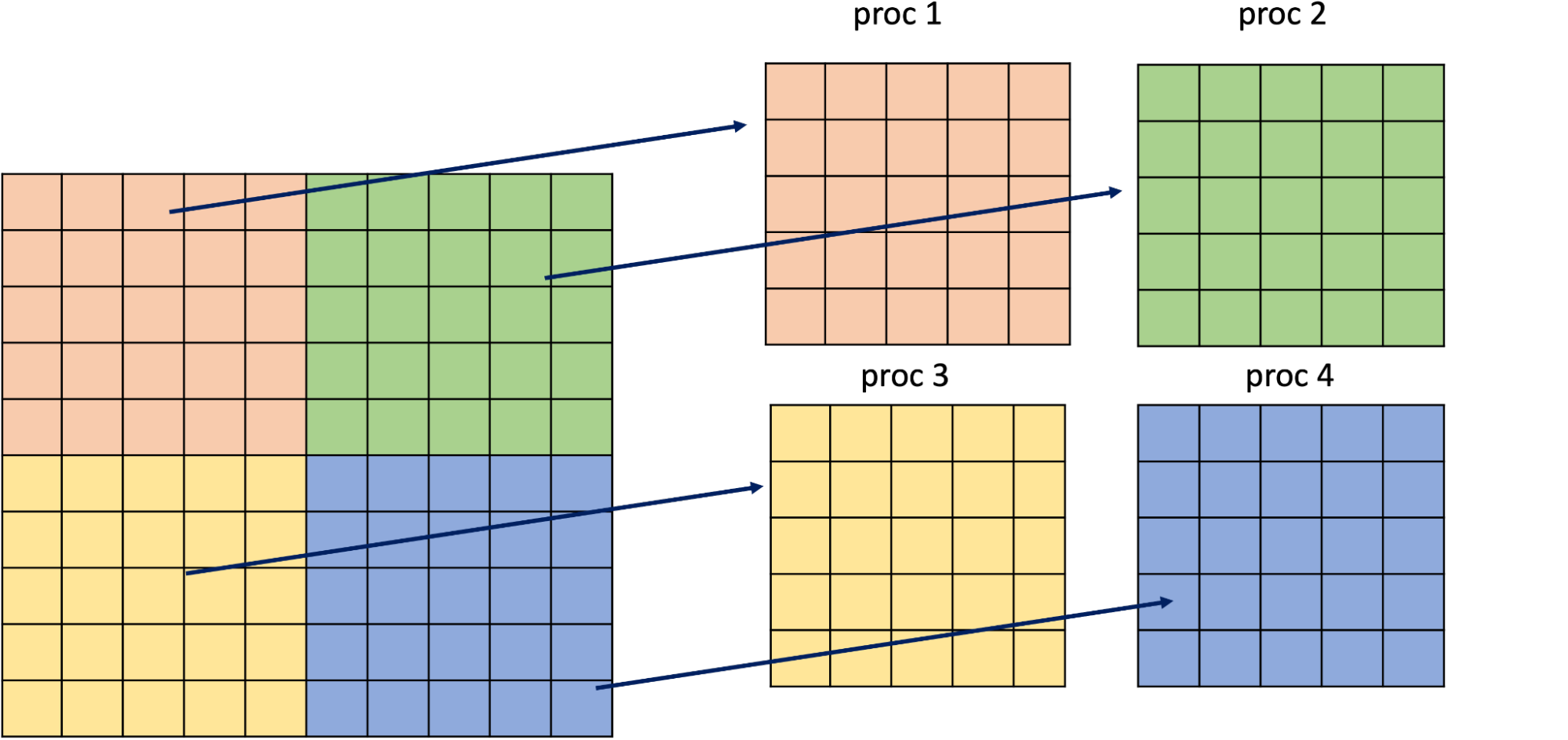

to partition data. Once data has been partitioned (an example of which is below), the launched task is broken

down into point tasks that operate on each piece of partitioned data on a separate GPU.

The body of the addition task, i.e. what code the task invocation actually runs, is defined in C++/CUDA to target GPUs. Psuedocode with many of the details of what this implementation looks like is shown below. These task bodies are invoked on each partitioned piece of a store.

class CuNumericAddTaskImpl : public LegateTaskImpl {

public:

static const int TASK_ID = CUNUMERIC_ADD_TASK_ID;

void gpu_variant(TaskContext& ctx) {

Store& A = ctx.inputs[0];

Store& B = ctx.inputs[1];

Store& C = ctx.outputs[0];

elemwise_add_cuda_kernel<<<...>>>(A.ptr(), B.ptr(), C.ptr());

}

};

Overall, the Legate Core provides a friendly programming model for distributed and heterogeneous machines, automating away many of difficulties of distributed programming. The main responsibilities left for a programmer are to describe what computation must be performed, and to provide fast kernel implementations. We hope that programmers can interact with the Legate ecosystem like they do with the sequential Python ecosystem today — libraries like cuNumeric and Legate Sparse are reused for the computations that they support, and programmers write small Legate extensions for the domain specific computations they need that are not supported by the general libraries.

Now that some components of writing Legate Core programs are concrete, I want to spend some more time

on the partitioning constraints discussed earlier, and how these constraints are critical to composing

independently written distributed computations. Partitioning constraints allow distributed programs to

“late-bind” the partitions of distributed data used for a computation, instead of specifying it as

part of the computation itself. The way that most distributed libraries today express computations

is through a method known as explicit partitioning, where the partitions of distributed data structures

are decided on a-priori and specified as part of the computation. In the explicit partitioning model,

libraries maintain partitions of distributed data structures, and use these partitions when launching their

computations. For example, a version of cuNumeric with explicit partitioning might represent a numpy.ndarray as a

(legate.Store, TilingPartition), where TilingPartition is a descriptor that represents the 2D tiling

of a matrix in the example shown above. Then, it would launch tasks that specify to use tiled partition,

something like the code shown below.

def explicit_partition_add(

A: Tuple[legate.Store, TilingPartition],

B: Tuple[legate.Store, TilingPartition],

) -> Tuple[legate.Store, TilingPartition]:

runtime = get_legate_runtime()

C = runtime.create_store(A[0].shape, A[0].dtype)

task = runtime.create_task(CUNUMERIC_ADD_TASK_ID)

task.add_input(A[1], B[1])

task.add_output(C.make_tiled_partition())

task.execute()

While this code seems reasonable, it is unclear how to make this code interact well with an independently written library that doesn’t know about the tiled partitioning convention. Consider the situation where the above code would interact with an external Legate library that decides to use a row-based partitioning for the matrices, and then called the element-wise addition operation. Since this explicitly partitioned element-wise addition has specified to use a tiled partition of each matrix, a large amount of data movement will be required to transition from the original row-based partitioning of each matrix to the tiled partition. Partitioning constraints instead enable the implementation of the library to leave the exact partitions to be used for each computation unspecified until runtime, where the Legate Core can see the context within each operation is invoked in. With partitioning constraints, this situation would be solved, as the constraint on the element-wise addition task would be satisfied for the row-based partitioning of each matrix. This would allow the partitioned stores to be used without any unnecessary data movement, which is critical for high performance. Legate Core contains a full set of partitioning constraints for describing many different kinds of partitioned data. This set includes constraints that broadcast different dimensions of stores across the machine, or relate the partitions of different stores together in data-dependent ways.

What’s next?

There is a large amount of active research and engineering going on within the Legate ecosystem.

- Techniques to further improve the performance of programs that compose multiple distributed libraries, such as fusion of tasks across libraries and better partitioning algorithms.

- Leveraging techniques like dynamic tracing to automatically optimize task-based computations.

- A proliferation of Legate libraries are being developed internally at NVIDIA. I can’t say which ones publicly, but there’s a flurry of activity!

We are looking for users and collaborators! We’re very interested in use-cases and applications for the Legate libraries that we have been building, as well as developers who want to build their own distributed libraries that can interoperate with the rest of the Legate ecosystem.

Related projects

There are many related projects that readers might be interested in. I’ve listed a few below:

- Legion and Realm are distributed, task-based runtime systems that Legate builds on top of.

- Regent is a high-level, implicitly parallel programming language for the Legion runtime.

- FlexFlow is a distributed neural network training and inference engine built on top of Legion.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Mike Bauer, Shriram Janardhan, Shriram Jagannathan and Jacob Faibussowitsch for feedback and comments on this post.

-

For an application with a nearest-neighbor communication pattern (communication complexity that doesn’t scale with the number of processors). Applications with communication complexities that scale with the number of processors are not expected to have flat weak-scaling curves. ↩︎