Update: We have extended the ideas in this post to generate optimal warp specialization strategies! See here.

Recently, I have been thinking deeply about warp specialization in the context of high performance kernels for modern Tensor Core GPUs like NVIDIA’s H100 and B200. My understanding of what warp specialization achieves has deepened and led me to the interesting question of: do we actually need warp specialization (and the complexity that it entails)? My conclusion is that the answer is indeed yes, but it might not be as mandatory as it seems. In this post, I’ll discuss when warp specialization is actually necessary, and describe the underlying trade-off space that I believe warp specialization resides within. While I will give some context on GPUs as necessary for discussing the topics at hand, this won’t be a tutorial – some experience with GPUs and parallel programming will be assumed.

Background

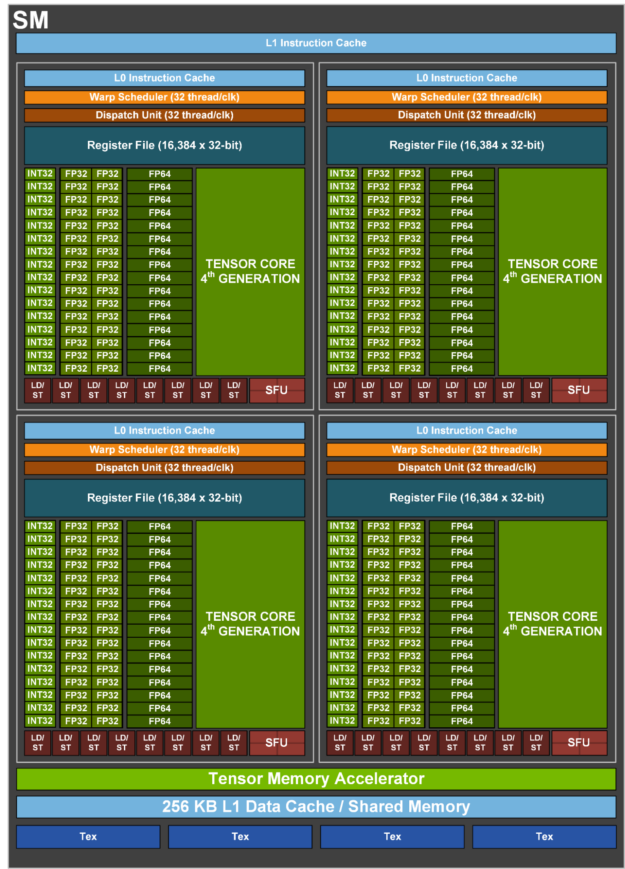

A GPU is a collection of processors called streaming multiprocessors (SM’s). For this discussion, we will focus on programming an individual SM. An SM is programmed with a hierarchy of threads, called a thread block. Threads in a thread block are further grouped into warps, which are groups of 32 threads. Each warp executes in a single-instruction-multiple-threads (SIMT) model. Each thread in a warp has its own instruction stream, and the warp issues one instruction on behalf of its threads in each issue slot. Performance is maximized (as discussed later) when all threads in a warp want to issue the same instruction at the same time. A Hopper SM (pictured below) has four execution contexts that can host an active warp, shown by the 4 quadrants.

At any cycle, at most 4 warps may issue instructions into the SM to execute. When a thread block contains more than 4 warps worth of threads (128), a hardware component called the warp scheduler selects 4 available warps to execute instructions.

A way to view an SM is as a collection of functional units (arithmetic units, load/store units, a Tensor Core) that are issued instructions at each clock cycle from the 4 execution contexts. These functional units have varying properties. Arithmetic units (ALU’s) perform individual math operations with short and fixed cycle latencies, Tensor Cores perform thousands of FLOPs in a single instruction with long cycle latencies, and load/store units (LSU’s) have long and unpredictable latencies due to interacting with the memory system. High performance GPU programs efficiently utilize the available functional units; compute-bound programs should use the Tensor Core and ALU’s at every clock cycle, while bandwidth-bound programs should keep the LSU’s busy to maximize bandwidth. To achieve high utilization, there must be work present for the functional units to perform (i.e. the floating point operations in a compute bound application should not be stalled waiting for loads to complete), and this available work must be issued into the functional units whenever they are available. This second aspect is where warp specialization becomes useful.

Warp Specialization

Warp specialization is a technique that became popularized through work on CUDA-DMA and the Singe Compiler, and is now a table-stakes technique for achieving high Tensor Core performance on Hopper and Blackwell GPUs. Warp specialization exploits the hierarchical grouping of threads within a thread block. When threads within the same warp diverge (i.e. branch on control flow in different ways), the SIMT nature of each warp results in performance degradation. Suppose that a warp reaches a branch where half the threads take the branch and the other half do not. The warp will now execute instructions from either side of the branch; when the warp selects an instruction from one side of the branch, the threads executing the other side do not progress. As a result, execution may take twice as long than if all threads in the warp took the same path through the branch. In the worst case, if all 32 threads in a warp take different control flow paths, the code could execute 32-times slower than the ideal! Unlike different threads within a warp, different warps within a thread block execute independently on separate execution contexts, which means that there is no cost when divergence occurs between warps. Warp specialization uses this property of warp divergence to restructure GPU programs. A standard GPU program executes the same logic on each warp, while a warp specialized program uses different warps to execute different components of the overall program. Let’s take a look at some of these warp specialization strategies in the aforementioned contexts.

The CUDA-DMA project proposed separating the loading of data from the GPU’s global (slow) memory to shared (fast) memory from the computation on data in the shared memory itself. CUDA-DMA separated the warps into memory loading warps and compute warps; the loader warps issue loads and signal the compute warps when the loaded data is available.

The Singe compiler targeted the generation of efficient combustion chemistry kernels. For the purposes of this post, these kernels essentially looked like large data-parallel computations (i.e. apply some function \(f\) to each element of an array) with a catch: computing \(f\) requires a large amount of intermediate state (numerous temporary variables in the chemical formulae). A straightforward implementation of these kernels requires too many registers to store the intermediate state and spills values to the stack, which lowers performance significantly. The annoying bit here is that the SM’s register file has enough space to store all the temporaries. However, the architecture provides each thread with a fixed number of accessible registers (for example, 255 per thread on Hopper). Singe used warp specialization to bypass the register-per-thread limit by partitioning the computation of \(f\) onto different warps. Concretely, suppose \(f(x) = 1 + x + 2 \cdot x + x^2 + 8 \cdot x^3\). Assuming a small register-per-thread budget, a warp specialized implementation of \(f\) might place the computation of \(1 + x + 2\cdot x\) onto warp one, and place \(x^2 + 8\cdot x^3\) onto warp two; the two warps would then communicate to sum the intermediate values.

Finally, warp specialization is used in high performance Tensor Core kernels targeting Hopper and Blackwell to interact with the accelerators appearing within the SM. On these GPUs, the SM contains accelerators that perform matrix multiplication (Tensor Core) and data movement to/from global memory (Tensor Memory Accelerator, or TMA). These accelerators offer instructions to multiply tiles of data or copy tiles of data to and from global memory. These accelerators are also asynchronous, where work on the accelerator is launched by a single instruction and then a blocking “wait” operation must be issued before using the results of the instruction. Specialized warps are used on Hopper and Blackwell to issue either TMA copies or Tensor Core matrix-multiplies. The TMA warp issue copies and notifies the Tensor Core warps when data is ready to be multiplied, and the Tensor Core warps notify the TMA warp when data has been consumed and the memory is free to use for more copies. This code looks something like:

if warpid() == LOAD:

for i, tile in enumerate(tiles):

if i > 0:

wait_for_tile_release()

async_tma_load(tile)

wait_for_tma_load()

signal_tile_loaded()

else:

for tile in enumerate(tiles):

wait_for_tile_loaded()

tile_data = get_loaded_tile(tile)

async_mma(tile_data)

wait_for_async_mma()

signal_tile_released()

Significantly more complex warp specialization strategies can be found in Tensor Core kernels that do more than just matrix-multiplication. For example, a high performance Flash Attention implementation on Blackwell uses at least 5 different kinds of specialized warps! In this Flash Attention implementation, there are warps for loading data, issuing matrix multiplication, computing softmax, scaling intermediate results, and storing data. As a result, the code is complex; the strategy itself is carefully constructed to yield high performance, and there is abundant cross-warp data movement and synchronization. Imagine the code above with 5 different warp cases and each cases signaling the others to proceed at different times!

Why is Warp Specialization Good?

The complexity of this Flash Attention implementation inspired me to take a step back and investigate the role of warp specialization in achieving high performance with the Tensor Cores. I had taken this need for warp specialization in Tensor Core kernels as a given; people who knew more than I told me that it was required, and I didn’t question (which is embarrassing for me, as an academic). In addition, other explanations of warp specialization out there often say vague things like “the architecture mandates it” or “it is needed for creating producer-consumer pipelines”.

Let’s derive from first principles when warp specialization is useful. An SM has some fixed number of compute resources available (i.e. ALU’s, LSU’s, a Tensor Core) and issue slots per clock cycle, regardless of how many warps a thread block uses. Therefore, a kernel has the same theoretical peak compute throughput and peak instructions issued per cycle on an H100 SM whether it uses 4 or 64 warps. So where are the benefits coming from? Consider two versions of a target program: one that is warp specialized and one that is not. The warp specialized kernel uses more than 4 warps to issue potentially different instruction streams into the SM, and the warps themselves are dynamically interleaved by the instruction scheduler. The standard program uses a single instruction stream issued from 4 identical warps. Clearly, warp specialization can only impact performance when the dynamically interleaved stream of instructions from more than 4 warps differs from the statically-specified instruction stream issued from the 4 warps in the standard program. The conditions that cause these proposed instruction streams to differ are the conditions where warp specialization can deliver increased performance. I believe there are three cases where this occurs.

The first case is simple to identify, and it is targeted by Singe: there does not exist a non-specialized version due to resource limitations! If the non-specialized version would use too many registers, predicates, or other warp-constrained SM resources, then warp specialization version allows for those resource constraints to be satisfied. Warp specialization due to resource constraints is commonplace in Hopper Tensor Core kernels, where accumulator tiles are split across multiple groups of warps to stay below the register-per-thread limit and spilling to the stack1.

The second case is a little trickier, since a non-specialized version of the target program must exist. This case involves discussing instruction scheduling. The SM contains several independent functional units, like FP units for floating point arithmetic and INT units for integer arithmetic, that may be executing operations at the same time. Consider a program with 2 floating point operations followed by 2 independent integer operations; a good instruction schedule would order the instructions to issue one floating point operation followed by one integer operation to utilize the FP units at the same time as the INT units. When a compiler (like NVCC) has accurate information about the number of cycles that each instruction takes, it can produce high quality static schedules that exploit instruction-level parallelism (ILP) to overlap independent instructions on different functional units. However, instruction scheduling becomes difficult for the compiler when the cycle counts of instructions are imprecise. Statically constructing a tight schedule when an instruction may take between 10-100 cycles instead of always 25 cycles is significantly harder. This is precisely the second case where warp specialization is useful: dynamic scheduling with the warp scheduler can gracefully handle variable instruction latency, which is common for memory-related operations. In this case, the statically-scheduled, non-specialized program must guess how long each variable-latency operation takes and construct a schedule that interleaves the variable-latency operation with other fixed-latency operations. When variable latency operations execute faster than expected, functional units end up under-utilized, and slower-than-expected operations result in stalls. A warp specialized implementation avoids the guesswork and interleaves instructions at runtime with the warp scheduler.

The third (and final) reason that I am aware of is related to the difficulties with variable-latency instructions, but gets further

into details about GPU architecture. To set the stage, we’ll contrast GPU architecture with that of general purpose CPU’s.

Modern CPU’s are out-of-order (OOO) issue processors; while a CPU processes a sequence of instructions, it finds ways to

dynamically reorder those instructions to exploit ILP while maintaining an illusion of sequential execution.

Concretely, if a CPU executes the instructions addf r1 r2; addf r3 r4; addi r5 r6; addi r7 r8 (the scheduling example from earlier)

it may automatically pull the independent addi instructions earlier and execute them while the addf instructions execute.

The compiler can help this scheduling hardware by partially reordering instructions, but the OOO capabilities of the processor do some heavy lifting.

The main downside of OOO is that the hardware required to implement it is costly — instead, GPUs

save chip area and energy by being in-order issue. When the GPU instruction stream contains

addf r1 r2; addf r3 r4; addi r5 r6; addi r7 r8, the instructions are issued to the SM in that order;

if the compiler didn’t perform any reordering, the SM will have under-utilized functional units. This problem is exacerbated when we introduce

the synchronization instructions that are used to interact with asynchronous accelerators (Tensor Core, TMA). These synchronization

instructions are essentially semaphores that put warps to sleep until the invoked accelerator

has completed. If these synchronization instructions are placed sub-optimally in the instruction stream, the warp may be blocked

from executing independent instructions until the operation being synchronized against completes. While compilers are pretty good

at scheduling, there are two difficulties that these synchronization operations introduce: 1) sychronization operations can often

act as code-motion barriers, as proving correctness of reordering operations (especially those that touch memory) around synchronization can be difficult, and 2) it can be difficult

for the compiler to track exactly what operation will resolve a synchronization point (i.e. which thread will release a lock).

Warp specialization allows the programmer to ignore the effects of this synchronization: by breaking the computation into separate warps, other warps

can immediately execute as soon as one warp blocks waiting on synchronization.

Summarizing the last few paragraphs, warp specialization can provide benefits when:

- An application’s resource requirements overflow the resources available to a single thread or warp.

- An application contains variable latency operations that need to be interleaved to maximize utilization.

- An application contains blocking synchronization that must be placed intelligently to avoid stalling.

Conditions 2 and 3 are inherently intertwined, as the source of both conditions is complications that make producing optimal static instruction schedules for in-order processors difficult. A view of warp specialization that gets at why it helps in this circumstance is that warp specialization essentially turns the SM from an in-order processor into a quasi-out-of-order processor, specifically at the specialization boundaries at each warp. The specialization points chosen by the warp specialization strategy indicate where ILP may be found (but is difficult to realize statically) while instructions within a specialized warp can be reasonably scheduled statically.

Testing the Hypothesis

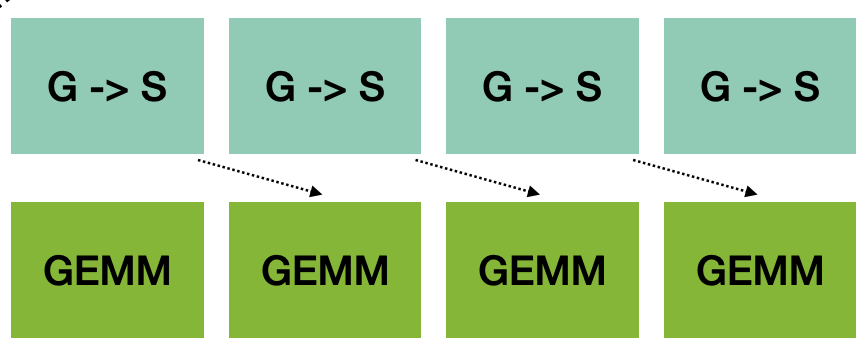

The previous section concluded that warp specialization is useful when 1) resource constraints mandate specialization, 2) variable latency instructions are difficult to statically schedule, and 3) blocking synchronization interferes with instruction issue. Let’s examine how (and if) these cases appear when developing a high performance H100 GEMM implementation for the problem size 8192x8192x8192. To do these experiments, I hand-modified code generated by the Cypress compiler; the generated code is too ugly to present, so I’ll discuss it at the level of vaguely-Pythonic psuedocode. An FP16 H100 GEMM roughly has the structure shown below.

An efficient GEMM orchestrates a software pipeline where at most PIPE outstanding

TMA loads of tiles from global memory to shared memory are pending, while GEMM operations execute

in parallel on the Tensor Core. In existing implementations, these two pipeline components run on

separate specialized warps. More detailed code than before describing a multiplication C = A @ B

is shown below.

# Initialize circular buffers holding PIPE tiles of A and B.

Abuf = [tile()] * PIPE

Bbuf = [tile()] * PIPE

if warpid() == LOAD:

for k in K / KTILE:

if k > PIPE:

wait_for_compute_iter(k - PIPE)

# The circular buffer index used by iteration k is k % PIPE.

async_tma_load(tile(A, k), Abuf[k % PIPE])

async_tma_load(tile(B, k), Bbuf[k % PIPE])

signal_when_load_complete_iter(k)

wait_all_mmas_done()

copy_C_shared_memory_to_global()

else:

C = init_accumulator()

for k in K / KTILE:

wait_for_load_complete(k)

async_mma(C, Abuf[k % PIPE], Bbuf[k % PIPE])

wait_for_mma()

signal_compute_iter_done(k)

store_C_into_shared_memory()

notify_all_mmas_done()

Let’s examine this code and understand which warp specialization conditions apply.

Tuning yields that the best performing tile size for the accumulator C is 256x256.

The accumulator C for H100 must be placed in the registers. Simple math

shows (256 * 256 FP16 elements / 128 threads (4 warps, 1 for each execution context) / 2 FP16 elements per 32-bit register = 256 registers) the accumulator

breaks the register-per-thread limit, satisfying condition 1: at least two groups of 4 warps are needed

to store C. What about the other two conditions? It’s not completely

clear that the synchronization or instruction scheduling is so hard that we need to move the

data loading to a separate warp. If we use a deep enough pipeline and synchronize only when

we already have pending work issued, we might be able to get away without warp specialization.

A non-specialized version of the GEMM above is shown below; some additional reordering and loop

peeling is required to start the pipeline, but the structure is similar.

Abuf = [tile()] * PIPE

Bbuf = [tile()] * PIPE

# Split the accumulator into 2 pieces for each

# group of warps to access.

C = init_accumulator(warpid())

# Issue the first PIPE outstanding loads.

for k in PIPE:

async_tma_load(tile(A, k), Abuf[k])

async_tma_load(tile(B, k), Bbuf[k])

# Main loop executes MMAs and loads into the future.

for k in [PIPE, K / KTILE):

# Logically, this MMA is for iteration k - PIPE.

wait_for_load_complete(k - PIPE)

async_mma(C, Abuf[k % PIPE], Bbuf[k % PIPE])

# This MMA wait will also include waiting on

# the paired cluster thread block.

wait_for_mma()

# Start the next load.

async_tma_load(tile(A, k), Abuf[k % PIPE])

async_tma_load(tile(B, k), Bbuf[k % PIPE])

# Perform the trailing PIPE MMA operations.

for k in [K / KTILE - PIPE, K / KTILE):

wait_for_load_complete(k)

async_mma(C, Abuf[k % PIPE], Bbuf[k % PIPE])

wait_for_mma()

# Copy out the accumulator to global memory (elided).

Unfortunately, it doesn’t perform as well as I hoped:

> ./gemm_nows_v1 --m 8192 --n 8192 --k 8192

MY_GEMM: [675868.8]GFlop/s (1.6268)ms

CUBLAS_GEMM: [805409.4]GFlop/s (1.3652)ms

This indicates that one of conditions 2 or 3 is applicable, causing under-utilization of either the TMA or Tensor Core. However,

all hope is not lost — what stuck out to me about this program was the wait_for_mma() operation inside the main loop,

which blocks the warp from issuing more loads until the pending MMA completes, which in turn

could lead to stalling the issue of future MMA’s. The solution here is to pipeline the loop again, where we also have some pending MMA’s

issued before the synchronization, hoping that the synchronization is now covered by already issued work. The code now looks something like this:

Abuf = [tile()] * PIPE

Bbuf = [tile()] * PIPE

# Split the accumulator into 2 pieces for each

# group of warps to access.

C = init_accumulator(warpid())

# Issue the first PIPE outstanding loads.

for k in PIPE:

async_tma_load(tile(A, k), Abuf[k])

async_tma_load(tile(B, k), Bbuf[k])

# Start the k=0 MMA, but don't wait for it.

wait_for_load_complete(0)

async_mma(C, Abuf[0], BBuf[0])

for k in [PIPE, K / KTILE):

# Logically, this MMA is for iteration k - PIPE + 1.

wait_for_load_complete(k - PIPE + 1)

async_mma(C, Abuf[(k - PIPE + 1) % PIPE], Bbuf[(k - PIPE + 1) % PIPE])

# Wait for the MMA from iteration k - PIPE, rather

# than the MMA we just launched (which is k - PIPE + 1).

wait_for_mma(k - PIPE)

# Start the next load.

async_tma_load(tile(A, k), Abuf[k % PIPE])

async_tma_load(tile(B, k), Bbuf[k % PIPE])

# Perform the trailing PIPE MMA operations.

for k in [K / KTILE - PIPE + 1, K / KTILE):

wait_for_load_complete(k)

async_mma(C, Abuf[k % PIPE], Bbuf[k % PIPE])

wait_for_mma()

Behold!

> ./gemm_nows_v2 --m 8192 --n 8192 --k 8192

MY_GEMM: [815881.7]GFlop/s (1.3476)ms

CUBLAS_GEMM: [807708.0]GFlop/s (1.3613)ms

We can achieve performance competitive with CuBLAS in this specific case without separating the TMA loads into a separate warp. For this problem instance, it was possible to mess with the loops by hand to avoid the effects of conditions 2 and 3. I’ll even argue here that while condition 1 was applicable, the resulting program isn’t even really warp specialized! The accumulator was split across multiple warps to fit within the register constraints, but the warps themselves are executing the same program. This exercise showed that for at least one problem size on H100, warp specialization is not required to hit peak performance.

Warp Specialization is a Trade-Off

In the previous sections, I laid out some principles for warp specialization, and then showed at least one useful case where we (or at least I) thought we needed warp specialization but achieved high performance without it. However, I don’t think the takeaway from this exercise should be that we should stop writing warp specialized programs. Instead, I think we should be viewing warp specialization as a point in a trade-off space over implementation choices for our kernels that have extreme performance demands (such as Tensor Core kernels). I argue that the implementations of high performance Tensor Core kernels navigate a trade-off space between the effort required to write a kernel and the effort required to develop compiler analyses that realize the intentions of the kernel writer. The cost-benefit analysis is about which allocation of effort allows us as GPU programmers to save more time overall.

If a human is not willing to put in a large amount of effort, there are several kinds of analyses a compiler could perform to achieve high performance. The first is high quality instruction scheduling by a low-level compiler like NVCC, which has the problems discussed earlier. Another direction is warp specialization performed by the compiler on a higher level language, something performed by the Triton or Cypress compilers. Compiler support for warp specialization seems promising, but compilers are not yet as good as humans at coming up with good warp specialization strategies; Triton even added a low-level language called Gluon so that expert humans could bypass the compiler’s warp specialization and do it themselves!

When a human is willing to put in a large amount of effort to achieve high performance, they can hand-write warp specialized programs and deal with the difficulties of scheduling and synchronization entailed by warp specialization. This direction naturally requires more kernel-writer effort, but makes the resulting program less dependent on the compiler’s instruction scheduling or warp specialization algorithms. A human may also consider writing a non-warp-specialized implementation, such as the GEMM kernel above that achieved high performance without warp specialization. This implementation also required some (but a very different kind of) kernel-writer effort to reorder loops to launch and synchronize operations in the right order. This reordering essentially “told” the compiler the right answer. When compared to a human-written, warp specialized implementation, the non-warp-specialized implementation may be more brittle; a different problem size or tile size may ruin the carefully crafted static schedule, while a dynamically scheduled, warp specialized implementation easily adapts.

The costs that define this trade-off space are changing with the capabilities of the architecture and the applications being developed. For example, a GEMM implementation on the Ampere architecture has similar complications as H100 around asynchronous and variable latency load instructions, but NVIDIA engineers found that high performance was achievable with acceptable complexity without warp specialization. A different example is an implementation of Flash Attention for the H100 GPU. In this application, the SM must perform large amounts of non-accelerator work (floating point reductions and exponential computations) while issuing and blocking on asynchronous accelerator work. Finding a static schedule that performs this interleaving perfectly is very difficult for a human or a compiler, hence why most H100 and later Flash Attention implementations are warp specialized. It’s not clear to me how far we can continue to push these directions for warp specialization without making the human effort too large to be worth the cost — as I mentioned before, the warp specialization strategies for efficient Blackwell kernels are really complicated. Both coming up with and realizing these strategies in correct code seems to be getting extremely difficult. Looking into the future, I can see a few (non-exhaustive) potential paths for where we might go with warp specialization: 1) GPU hardware may become easier to program and need warp specialization in fewer cases (unlikely), 2) compiler algorithms for warp specialization will continue to improve and achieve parity with humans, or 3) systems software will be developed that removes many of the footguns of writing warp specialized code.

Acknowledgments

This post was put together after conversations with several colleagues and mentors: Rupanshu Soi, Fredrik Kjolstad, Alex Aiken, Michael Garland, Michael Bauer and Duane Merrill. Michael Garland, Michael Bauer and Rupanshu Soi gave helpful comments to improve this article. Thanks to Manya Bansal for giving me a push to condense these thoughts and release them into the wild. Nash Brown caught some typos in the pseudocode.

-

Spilling any registers to the stack in high performance linear algebra kernels on GPUs can result in significant performance degradation. Serious care is taken to optimize code and tune parameters to fit within register limits. ↩︎